The Omicron Variant and The Infantilization of Africa

Blessing Nwodo laments the doltish, and oft harmful, prejudice towards Africa and its people.

Weeks ago when South Africa was hit with a travel ban for reporting the detection of the Covid-19 Omicron variant, I knew Nigeria, the dubbed giant of Africa, would be next. A stone thrown on the playground, is unlikely to miss the largest child.

Every country has its buried stash of skeletons, and the African continent is not the sole cemetery of the planet.

The origin of Omicron is unclear. Even though it was found in about 24 countries when scientists began searching, travel bans were issued to southern Africa alone, even in countries with no Omicron cases. Africa is the scapegoat child who receives the most punishment from the teacher for a mishap committed by everyone in class. The entire continent even before Covid-19, is seen as the sickly pupil always taking permission to go to the hospital, before going home to a confined mud hut, surrounded by fifty-four family members coughing on each other all day, spreading diseases as a show of affection.

I began my Masters in Fine Arts online at the Canadian University of Guelph in September. While others are in class, I am a face on a screen, tuning in more than 5000 miles from across the ocean, struggling to hear what others are saying.

I was supposed to have gotten my study permit in August after applying before the deadline in May, but I received anxiety fueled waiting instead. Not only were processing times slower than usual because of Covid-19, uncertainty clung to me like a damp shirt soaked with sweat. My future was in the hands of people to whom I was merely a figure on a series of documents. I paid fees, kept attending classes and juggling school responsibilities, creative writing tasks, family obligations and life's obstacles in general with work, afraid that all that effort would mean nothing if I got a refusal, unable to make proper plans, or say yes to things like a five week physiotherapy session for my hurting knee, because Canada could call anytime. At the end of November after I had unpacked my bags and allowed my mental health a break from the seemingly endless stasis, I received my permit. Days later, Omicron knocked on the door with a giant creepy smile and asked me: "Where do you think you're going?"

I applied for a study permit in May, but the actual preparation began months before, because trying to get a visa as an African is like being told to wear shoes with soles fashioned from sharpened nails, then asked to jump through obstacle courses constructed in the middle of a bubbling hot volcano with a smile on your face and grace in your movements. One of them is paying for, and writing an exam native speakers would fail if taken without preparation, to prove you can speak English, after your country was colonized by the British and students are punished in schools for speaking their native languages.

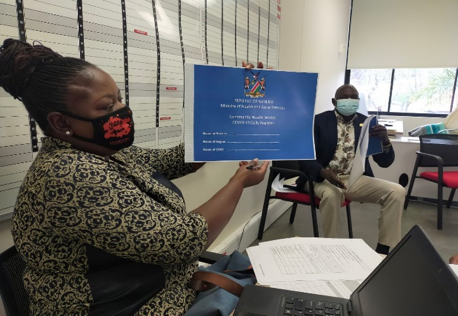

I received my first Oxford Covid-19 vaccine in March and went back for the second dose in June, on the exact date I was told to return. Now, I am told that Nigeria received vaccines so close to their expiration date, a lot of them weren't dispensed. I'm left to wonder. Did I get injected with expired vaccines the second time or both times? As a fully vaccinated person, I could enter Canada and may not have to quarantine for 11-14 days. I say may because I am still African, the sick child, and rules that apply to others may not apply to me.

Quarantining is not the problem, spending outrageous unplanned amounts to do so as an international student is. Still, I was vaccinated. Now, I might as well not be, because being fully vaccinated means you might as well be unvaccinated. What a great way to encourage the unvaccinated to do so immediately. We want the world to stop being suspicious of vaccines? The best way to do that is hoard vaccines, beg and offer incentives to privileged people to come out and protect themselves, and when they petulantly turn up their noses at them, quickly dispense them to other countries close to their expiration date, then tell them it could be expired after some do and the bubble wrap of protection was in fact, imaginary.

As a Nigerian child, my impressionable mind amplified the cotton candy stories America told about itself. To us kids brought up with the white man's religion, the biblical land of milk and honey may have been unattainable, but America was the concrete manifestation of the promised land. Until we grew up and learnt that America's story is that of the Dolphin, savior of drowning humans but also the rapist of the ocean. The perception of Canada on the other hand, is that they're kinder Americans, a well refined version of the polite British front—a strong contrast from the shared colonizer history and scores of dead Native American children found in schools. The entire continent of Africa, however, remains a snot-nosed child carrying around a dirty ball of Ebola, sent to her room and grounded by her parents.

Storytelling is power. Stories are so intrinsically tied to our core as humans that even while sleeping, our mind stays awake, telling us stories, and we call them dreams. The stories that we tell about people are the reason why certain groups are invited to sit at the cool kids table in a school cafeteria, while others ostracized, eat alone. Every country has its buried stash of skeletons, and the African continent is not the sole cemetery of the planet. Despite the grim, spotlighted stories; the laughter, ingenuity, rich culture, talent and tenacity of the African people shine like the luminously blazing ball of energy, hanging in the deeply dark backdrop of space.