Dwelling Places

Rita Nkemba is the Founder and Acting Country Director of Dwelling Places, an organization that rescues street-connected children in Uganda, and reintegrates them into society.

I’m a social worker and I love children. I have two biological children, but my husband and I have raised 21 children in foster care. Many of them are now adults. Growing up, our home was never about me and my six siblings. We always had cousins or friends staying with us, and it was never an issue. That’s why, for me, having an extra person to take care of is natural.

In 2002, I started Dwelling Places, an organization that rescues, rehabilitates and reintegrates street-connected children. These are kids who end up on street as a result of bad parenting, family conflict and child trafficking.

When COVID-19 happened, it was frightening. Every organization was downsizing and it seemed like the automatic thing to do. It was like the world was closing down.

It was the beginning of the year. We hadn’t received many commitments for funding. Two big donors had promised us funds but all of a sudden, they halted their funding due to the uncertainty brought about by the pandemic. We had funding for school fees, and for the care of the 453 children that we support. Schools had closed. We had to be creative.

Importantly, we didn’t want children in our care, who have already been on the street and gone through that suffering, to go back to the street. We abandoned our work plans and focused on keeping these 435 children at home. A funder came through to support our advocacy work and through this, we managed to get our staff, who had become redundant, back on board.

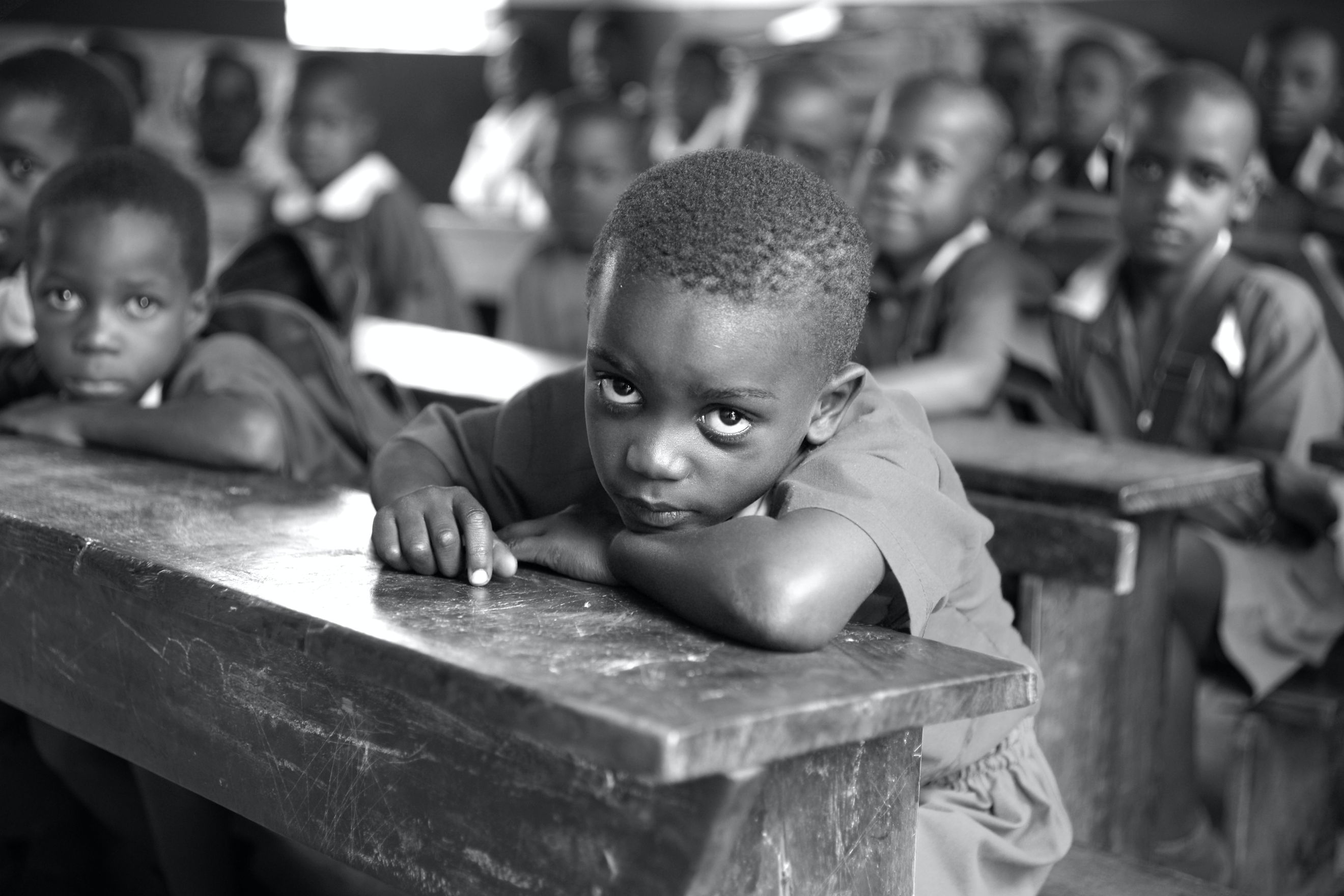

When schools closed due to COVID-19, we picked the booklets that the government had been distributing to facilitate remote learning. Many teachers were out of work, so we recruited them and enabled them to go into the communities and teach children in clusters. This clustered learning benefited the children in our care and children from other communities.

Of course, the definition of school changed from the classroom to the home and in the community. Our community-based tutoring took place in two major areas where our children are; Karamoja sub-region in Northeast of Uganda and within Buganda (central Uganda).

In partnership with the Buganda Kingdom and through its clan system, we saw an opportunity to help children get some kind of identity. Most of the children who have been on the street lack identity. It doesn’t matter if you are from another part of the country, as long as you are willing to identify as a Muganda, the kingdom will affiliate you to a clan.

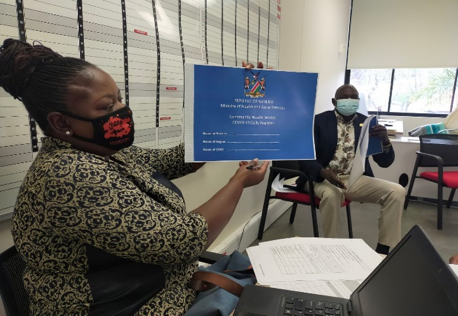

The kingdom also helped us utilize teachers in its schools. On top of this, they provided booklets with educational content. A teacher would go into a community and teach a cluster of about 10 children. Masks were distributed and physical distance was observed.

This model was not easy especially in slum communities but the teachers still went there. A total of 238 children within the central region benefited from this tutoring model. It was challenging for the learners in secondary school and college because they had various course units which differed from student to student.

Despite the disruption occasioned by the second wave of infections, the parents of these children picked up where the teachers had stopped. The booklets had been distributed among the children and they continued to learn under their parents’ supervision.

Closing schools introduced another dynamic. Parents encouraged their children to partake in economic activities like selling foodstuffs and other items in order to earn some income so as to sustain the family. Sadly, girls began to encounter risks while vending food on streets. Risks like men taking advantage of them to abuse them sexually.

This challenge birthed the idea of supervised work. This supervised work also included an element of learning. We advised parents to supervise these children by the roadside where they are selling their foodstuffs, and to allow them to carry their learning booklets. That way, children continued studying during those times when they were not attending to customers.

Dwelling Places also got parents engaged in economic empowerment by getting them together to save some money. Through these parents’ clusters called Village Savings and Loans Associations, they shared their experiences but also gained access to small loans that would enable them to earn a livelihood. In the central region, thirty families benefited from this.

In Karamoja, the community-based tutoring had bigger success. Traditionally, in Napak district, households are formed in ‘manyattas’, big compounds made up of several households. This made clustered learning easy. It was easy to send teachers in these clusters. Across Karamoja, 20 clusters of parents under Village Savings and Loans Associations have managed to save up to $5,555 to date. For many of these parents, they borrow to sell silverfish, charcoal, goats, and engage in other business ventures.

In as much as COVID-19 has had lots of negatives, the lockdown birthed creativity. And if we pick lessons from this, there are many good innovations that can continue, especially at the family level and in terms of keeping children off the streets, parenting and learning.

For me, the biggest lesson from the last one and a half years has been that all things are possible. There’s no situation where there’s nothing that can be done. It is still possible to keep children off the street if we support them to stay in school. And school, as an institution, can actually be at home. It doesn’t matter if a parent hasn’t been to school, but if you show them how to teach their kids, they will be able to keep them off the streets.